Chapel Hill, NC

Cleveland, OH

Austin, TX

Washington D.C. area

Scottsdale, AZ

Seattle, WA

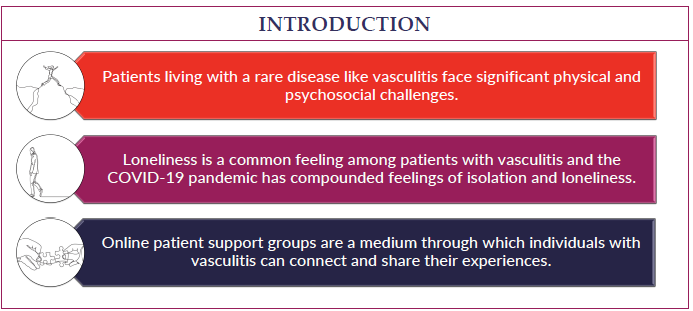

We are you. We are patients with vasculitis, care partners, friends, family, physicians, and researchers advocating for early diagnosis, better treatments, and improving quality of life for people with vasculitis.

Explore. Learn. Download Resources. Join a Support Group.

Pediatric Vasculitis

About Polyarteritis Nodosa (PAN)

Last Updated on February 5, 2024

Polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) is a form of vasculitis that can occur in two distinct forms: cutaneous PAN (where inflammation involves primarily the vessels of the skin) and systemic PAN (where the entire bed of small to medium arteries may be involved). Some people believe that these two forms represent the two ends of the spectrum of PAN. In both cases, inflammation (-itis) of primarily medium and occasionally smaller arteries occurs, leading to restricted blood flow to the organs and tissues that these arteries supply, including the skin, joints, kidneys, gastrointestinal tract, heart, lungs and brain, among other organs.

Polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) is a form of vasculitis that can occur in two distinct forms: cutaneous PAN (where inflammation involves primarily the vessels of the skin) and systemic PAN (where the entire bed of small to medium arteries may be involved). Some people believe that these two forms represent the two ends of the spectrum of PAN. In both cases, inflammation (-itis) of primarily medium and occasionally smaller arteries occurs, leading to restricted blood flow to the organs and tissues that these arteries supply, including the skin, joints, kidneys, gastrointestinal tract, heart, lungs and brain, among other organs. Cutaneous PAN involves primarily the skin and joints, and may follow a relatively mild course. Systemic PAN affects the body more extensively, and can cause symptoms such as fever, fatigue, weakness, weight loss or poor growth, muscle and joint aches, skin abnormalities, abdominal pain, and peripheral nerve injury which could cause areas of numbness in the legs and arms. When the kidney is involved, as it often is, high blood pressure can result. In some people, the vessel damage leads to weakened artery walls, which may then balloon out, forming aneurysms.

Prompt diagnosis and treatment are essential to avoid serious complications of PAN. Initially, corticosteroids are often used in high doses along with other medications to suppress inflammation and immune-mediated attack on the vessels. After an initial response to treatment, PAN may remain quiet in some individuals, or follow a course in others that may have periods of relapse and remission. Therefore, close ongoing medical observation is important over long periods of time. In cutaneous PAN, where just skin and perhaps joints are involved, treatment usually leads to a lasting remission.

Most children who develop PAN have been previously healthy. It is not known what triggers the immune system to go awry and attack one’s own blood vessels. In some cases, a recent infection appears to trigger PAN. Streptococcus has been associated with the development of PAN, especially the cutaneous form. Hepatitis B or other viral infections may trigger PAN in some individuals. In others, it might be a reaction to medication or unknown immune triggers. People of Middle Eastern origin with a mutation in the gene encoding an inflammatory protein called pyrin have a higher rate of PAN and some other vasculitis conditions than people without these mutations. Another genetic risk factor involves a gene that encodes for adenosine deaminase 2 (ADA2). People with a mutation of this gene may present with a clinical disease that looks very much like PAN. The onset of disease in individuals with a deficiency of ADA2 (DADA2) almost always occurs during childhood.

In most cases, though, we do not know what causes PAN.

Polyarteritis nodosa is a rare disease with an estimated annual incidence of 3 to 4.5 cases per 100,000 persons in the United States. A study from southern Sweden reported the annual incidence for PAN was 7/100,000 children. Asian populations appear to have a higher incidence. It may be more common still in Turkey and Israel, likely because of the high rate of carriers for mutations in the pyrin gene. It is most common in adults between the ages of 45 to 65 years, but PAN has been reported in early infancy as well. Boys are more commonly affected than girls.

PAN can affect almost any organ system, and the symptoms can be very different from one person to another. Often, the first symptoms are non-specific, with patients reporting fever, night sweats, loss of appetite and poor weight gain or even weight loss, rash, and severe muscle and joint pains evolving over a period of weeks to months.

Common signs and symptoms

- Fatigue

- Loss of appetite

- Numbness or tingling in hands or feet

- High blood pressure

- Blood in stool

- Chest pain

- Trouble breathing

- Fever

- Lacy rash, skin nodules or ulcerations

- Swollen lymph nodes

Other reported signs and symptoms

- Testicular pain in boys

- Abdominal pain

- Inflamed mucous membranes

- Sudden loss of strength of hands or feet

- Spleen swelling and tenderness

- Strokes and encephalopathy with brain malfunction and seizures

- Poor blood flow/perfusion of fingers and toes

- Nodules in the subcutaneous fat layer

Because most patients’ symptoms include fever and malaise, extensive testing is needed to be sure infection is not the cause. Unfortunately, there is not a single lab study that makes the diagnosis of PAN.

- Laboratory studies: Blood and urine cultures are often performed to rule out infection as a cause of the fever and other symptoms. A complete blood count (CBC) often shows anemia. Non-specific tests for inflammation, such as the sedimentation rate (ESR) and c-reactive protein (CRP) are often elevated in active PAN. A full chemistry panel is performed to assess kidney and liver function. A urinalysis is performed to check for blood or protein in the urine. Sometimes, a gene study to look for the presence of DADA2 will be performed in children presenting with PAN symptoms.

- Imaging studies: X-rays or other specialized imaging studies, such as ultrasound, angiograms and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA), are needed to visualize the affected vessels.

- Biopsy: If uncertainty remains about the cause of symptoms, a biopsy of an affected vessel or tissue usually pins down the diagnosis.

Treatment for PAN begins with corticosteroids (either oral prednisone or prednisolone, or IV methylprednisolone) to control the inflammation, but, in severe multi-organ involvement, corticosteroids are usually combined with an immune-suppressing drug called cyclophosphamide which will lower the number of inflammatory cells that can do damage to the arteries. Other immunosuppressants, such as methotrexate, azathioprine or mycophenolate mofetil, may be used to induce or to help maintain immunosuppression. Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), an infusion of pooled antibodies may be beneficial in some cases. In refractory cases, i.e., those not responding to the treatments above, medications such as rituximab or other biological medications may be given. Complications, such as hypertension, are also treated with medication. If the PAN is related to hepatitis B, antiviral medications and sometimes plasma exchange are employed. Children with cutaneous PAN usually respond well just to corticosteroids. If a preceding streptococcal infection was implicated as a possible trigger of PAN, then antibiotic (often penicillin) prophylaxis may be considered.

In 2021 the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) published guidelines for the management of certain vasculitides, that were also endorsed by the Vasculitis Foundation (VF). Clinical practice guidelines are developed to reduce inappropriate care, minimize geographic variations in practice patterns, and enable effective use of health care resources. Guidelines and recommendations developed and/or endorsed by the ACR are intended to provide guidance for particular patterns of practice and not to dictate the care of a particular patient. The application of these guidelines should be made by the physician in light of each patient’s individual circumstances. Guidelines and recommendations are subject to periodic revision as warranted by the evolution of medical knowledge, technology, and practice.

The strong immunosuppressants used to treat the inflammatory reaction in PAN have possible side effects, including lowering your body’s ability to fight infection, weakening of the bones (osteoporosis), high blood sugar, altered fat metabolism, acne and others. It is important for your doctor to closely monitor your progress and adjust your medication to the lowest effective dose to control the disease. Prevention of infection is also very important. Talk with your doctor about ways to do this including immunizations, avoiding ill contacts, and sanitizing surfaces that put you at high risk for infection.

A variety of complications may occur, depending on the organ systems involved. Aneurysms in the arteries that lead to the kidneys, liver, or intestines can cause impaired kidney function, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting or GI bleeding. Affected arteries could develop blood clots, leading to organ injury such as myocardial infarction (heart attack), or loss of skin and subcutaneous tissue. Interestingly, the lungs are often spared in PAN.

Even with effective treatment, the disease may be characterized by fluctuations in disease activity, with periods of flares and remission. If initial symptoms return or worsen, or if new symptoms develop, report this to your physician as soon as possible. Regular check-ups, ongoing lab tests and imaging are important to detect relapses or new organ involvement.

Compared to adults with PAN, children usually start with healthy blood vessels, so the vessel inflammation and possible resulting vessel injury is often better tolerated in children. Children have a wonderful ability to heal and to rebound from even very severe illness. In small studies comparing children with adults, children are more likely to have the milder cutaneous PAN form than adults and were less likely to have kidney and brain involvement than the adult patients. The mortality rate in children was very low (0%), but it was 13.6% in adults in one study of 22 adults and 15 children. [Erden A, Batu E, Sonmez HE, et al. Int J Rheum Dis. 2017 PMID: 28626961; DOI: 10.1111/1756-185X.13120]. In a larger report of 69 children with PAN, the relapse rate was reported to be 35%, with a mortality rate below 5%. [Eleftheriou D, Dillon MJ, Tullus K, et al. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2013, 65:2476-2485. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.38024].

Effective treatment of PAN will require the coordinated care of a team of medical providers and specialists. In addition to your primary care provider, you will need to be followed by a pediatric rheumatologist. You may also need to see other specialists: dermatologist (skin), nephrologist (kidneys), cardiologist (heart specialist), or others as needed, depending on the organs involved. You might also benefit from a physical or occupational therapist at points in your course. Chronic illness and medication side effects can put a lot of stress on a child or teen, so your needs might include an educator or a psychotherapist to assure the best outcomes.

It may be helpful to keep a health care journal to help remember your team members. In it, you can track medications and doses, your symptoms, test results, and file notes from doctor appointments all in one place. To get the most out of your doctor visits, make a list of questions beforehand and bring a supportive friend or family member to provide a second set of ears and to take notes.

Remember, it’s up to you to be your own advocate. If you have concerns with your treatment plan, speak up. Your doctor may be able to adjust your dosage or offer different treatment options. If a medication makes you feel ill, discuss it with your doctor. Also, it is always your right to seek a second opinion.

Forty years ago, PAN was a fatal disease in many cases, especially systemic PAN. Now, it is a chronic condition that can usually be well-controlled with immunosuppressant medication, but that means you must take more precautions than other children and teenagers who do not have a chronic disease. This can frustrate and discourage many people, but the upside is that, in most situations, a full, productive life is possible with the help of your medical team. Sharing your experience with family and friends, connecting with others through a support group, or talking with a mental health professional can help.

There is a lot of research and progress world-wide to help understand what causes PAN, the genetics that might pre-dispose someone to getting the disease, and the mechanisms of the vasculitis. This has led to improvement in treatment, and therefore survival rate and improved quality of life. Still, much remains to be learned about PAN, but with the research underway leading to clinical trials of newer medications, more progress is just around the corner.

Information on current clinical trials is posted on the Internet at www.clinicaltrials.gov. All studies receiving U.S. government funding, and some supported by private industry, are posted on this government website. For information about clinical trials being conducted at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in Bethesda, MD, contact the NIH Patient Recruitment Office:

- Tollfree: (800) 411-1222

- TTY: (866) 411-1010

- Email: [email protected]

For information about clinical trials sponsored by private sources, contact: www.centerwatc.com

PRINTO (Paediatric Rheumatology International Trials Organisation) has a website with information in many languages about most pediatric rheumatic and autoimmune diseases. To choose a language other than English, go to PRINTO.it, scroll down to select the country where that language is primary (for English, choose UK), and choose “information on paediatric rheumatic diseases.” At the bottom of the page, choose “first section.” From there, click on “rare juvenile primary systemic vasculitis.” Alternatively, copy and paste the following address into your browser:

https://www.printo.it/pediatric-rheumatology/GB/info/9/Rare-Juvenile-Primary-Systemic-Vasculitis.

PAN Videos

ACRVF Guidelines Conf PAN Breakout