Chapel Hill, NC

Cleveland, OH

Austin, TX

Washington D.C. area

Scottsdale, AZ

Seattle, WA

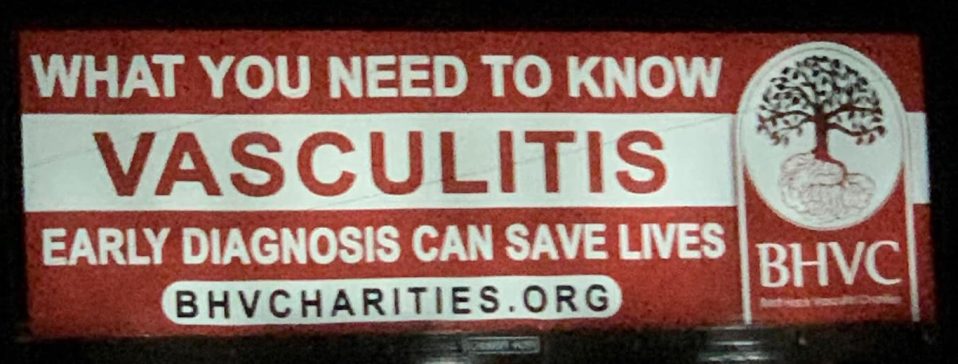

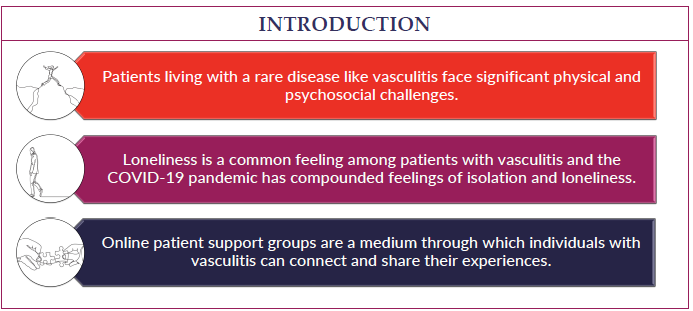

We are you. We are patients with vasculitis, care partners, friends, family, physicians, and researchers advocating for early diagnosis, better treatments, and improving quality of life for people with vasculitis.

Explore. Learn. Download Resources. Join a Support Group.

Pediatric Vasculitis

About Eosinophilic Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis (EGPA)

Last Updated on February 5, 2024

Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA), formerly known as Churg-Strauss syndrome, is one of several types of autoimmune disease in which your body’s immune system, which is meant to protect you, gets confused and attacks its own blood vessels (arteries, arterioles, veins, venules, capillaries) to cause inflammation. This is known as vasculitis. EGPA usually affects smaller- to medium-sized blood vessels and commonly causes inflammation and possible damage to the lungs, sinuses, skin, heart, intestinal tract, kidneys, and nerves.

Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA), formerly known as Churg-Strauss syndrome, is one of several types of autoimmune disease in which your body’s immune system, which is meant to protect you, gets confused and attacks its own blood vessels (arteries, arterioles, veins, venules, capillaries) to cause inflammation. This is known as vasculitis. EGPA usually affects smaller- to medium-sized blood vessels and commonly causes inflammation and possible damage to the lungs, sinuses, skin, heart, intestinal tract, kidneys, and nerves.

EGPA is one of 3 types of vasculitis in which the immune system attacks small- to medium-sized blood vessels and where we have identified that the immune system frequently makes an antibody as part of its “army”. This antibody is called anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) and has a role in causing the inflammation and damage. The other two types of ANCA-vasculitis are granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) and microscopic polyangiitis (MPA). Patients with EGPA differ from GPA and MPA in that they less often have ANCA present, whereas eosinophils (types of white blood cells) are often increased as part of the immune system “army” that causes inflammation. EGPA is the rarest type of ANCA-associated vasculitis, and is seen primarily in people who have asthma and allergies.

While the name is complicated, eosinophilic refers to increased eosinophils, granulomatosis refers to the formation of granulomas (a pattern of inflammation), and polyangiitis refers to inflammation of blood vessels.

EGPA is a serious condition that requires treatment by doctors who specialize in the immune system (rheumatologists, immunologists), kidney disease (nephrologists), lung disease (pulmonologists), and head and neck disease (ear, nose and throat specialists). Treatment typically includes medication that calms the immune system so that it no longer attacks itself. Fortunately, treatment has come a long way and can allow people to live full lives with ongoing medical care.

The cause of EGPA is unknown; however, it is likely a combination of genetic factors (although it does not seem to recur in families) and environmental triggers (infection, inhaled particles/allergens, medications, etc.). EGPA is not preventable or contagious. Researchers are actively searching for the cause.

EGPA can occur in anyone, no matter their age, race, or sex. The disease is much more common in adults (the average age of diagnosis is 50 years old) than it is in children. It appears to occur equally in males and females. The disease is considered very rare and estimated to occur in 1 to 3 out of 100,000 adults per year in the USA, and in 2.5 out of 100,000 adults per year worldwide. The frequency in children is not known.

The symptoms of EGPA vary from person to person and range from mild- to life-threatening, depending on which parts of the body are affected. Two people with EGPA will likely have different “patterns” of symptoms. Symptoms typically develop over a long period of time, starting with asthma and allergies. Eventually there is an emergence of increased blood eosinophils (a type of white blood cell assisting the immune system). Then, over weeks or months, additional symptoms may develop. After asthma and allergies, the more common symptoms which may occur include:

- Fever

- Decreased energy

- Weight loss

- Muscle and joint pain

- Allergic rhinitis

- Nasal and sinus polyps (growths)

- Nose bleeds or nasal congestion

- Chest pain or palpitations (heart beat you can feel)

- Trouble breathing or running out of breath easily

- Coughing, with or without blood

- Rashes

- Numbness or tingling of body parts, such as hands or feet

- Weakness in a body part, such as hands or feet

- Abdominal pain and possible bloody stools

- Dark, red, or foamy urine

There is no single test to diagnose EGPA; rather, the diagnosis is reached by evaluating clinical symptoms with results of lab tests and other investigations, similar to putting together pieces of a puzzle. EGPA is initially suspected in a person who has some of the clinical features mentioned above. In addition to information gained by performing a detailed medical history and physical examination, more is learned by evaluating blood and urine tests, imaging studies, and/or obtaining a sample (or biopsy) of affected tissue. Some children require admission to the hospital for diagnosis in order to urgently exclude more commonly occurring inflammatory conditions or infections with similar features. Other children can be diagnosed over the course of multiple clinic appointments.

- Blood tests: A positive ANCA test contributes toward the diagnosis but is positive in only approximately 40% of people with EGPA. Additional blood tests that may be helpful in EGPA include a complete blood cell count (CBC) with eosinophil levels and markers of inflammation: erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and c-reactive protein (CRP).

- Urine tests: Urine samples can be checked for protein or blood which, when present, could indicate inflammation of the kidneys.

- Imaging studies: X-rays, computed tomography (CT) scans, or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans of different body areas may help identify the involved sites and severity of inflammation or damage, especially in the lungs or sinuses.

- Tissue biopsies: It is often necessary to perform a surgical procedure to remove a small sample of tissue from an affected organ so that it can be seen under a microscope. This is most often necessary if the diagnosis of EGPA remains unclear.

- Pulmonary function tests (PFTs): A child may be asked to complete a breathing test to determine how well their lungs are working to expand and exchange oxygen.

- Bronchoscopy: A pulmonologist may need to use a scope to take a closer look at the upper airways and lung passages. They may also take a sample of fluid for analysis.

- Nerve conduction studies: A neurologist may need to conduct nerve signal testing if a child’s main symptom is numbness, tingling, or weakness in a particular limb.

- Echocardiogram: An ultrasound of the heart should be performed to screen for inflammation in anyone in whom a diagnosis of EGPA is being considered.

The overall purpose of treatment is to calm the body’s immune system so that it no longer attacks itself. This is known as “immunosuppression.” For all medications, the risks of treatment (actual or potential side effects) should be weighed against the risks of not treating the disease. The medical provider who explains this to the family will require an understanding of the severity of the patient’s disease, and knowledge of the potential risks and benefits of different treatment options. The degree of treatment will depend on whether the child has mild or severe disease. The goal of treatment is to quiet inflammation as quickly and as effectively as possible. This is most often achieved with high-dose corticosteroids, which may be in the form of prednisone (oral tablets), prednisolone (oral liquid), and methylprednisolone (given through an IV). Corticosteroids act quickly to prevent progression of EGPA; however, there are many side effects (see next section). Therefore, an additional medication (also called a “steroid-sparing agent”) is often started that may have less side effects but may take longer to start working. As this medication kicks in, the corticosteroid dose is steadily reduced and ideally stopped completely. Possible steroid-sparing agents may include rituximab, cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, azathioprine, and mycophenolate mofetil. Benralizumab and mepolizumab are more recently developed medications which have been used primarily in adults. They are unique in that they directly block the eosinophil army and therefore are useful in EGPA but not in other types of ANCA-associated vasculitis (GPA or MPA). These medications have not been directly studied in children with EGPA, however data from studies of these medications in adults with EGPA and on children with other diseases has provided helpful insight. Children may also require inhaled medications to help control their asthma.

Learn More About Treatments for Vasculitis

In 2021 the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) published guidelines for the management of certain vasculitides, that were also endorsed by the Vasculitis Foundation (VF). Clinical practice guidelines are developed to reduce inappropriate care, minimize geographic variations in practice patterns, and enable effective use of health care resources. Guidelines and recommendations developed and/or endorsed by the ACR are intended to provide guidance for particular patterns of practice and not to dictate the care of a particular patient. The application of these guidelines should be made by the physician in light of each patient’s individual circumstances. Guidelines and recommendations are subject to periodic revision as warranted by the evolution of medical knowledge, technology, and practice.

While all medications for EGPA work by ‘calming the immune system’ the flip side of this is that they may decrease the body’s ability to fight infections. It is important to consider vaccinations prior to and during treatment if possible, including the vaccines for covid-19, influenza, and pneumonia. The shingles vaccine should be considered if over 18 years of age. A medical provider should inform families of the possible side effects for prescribed medications. Corticosteroids are particularly known for causing side effects if given long-term, and in addition to immune suppression, some of these include bone weakness, elevated blood pressure, elevated blood sugar, trouble sleeping, increased appetite, or irritability. Particularly troublesome in children and youth is altered body image that can occur because of delayed growth, delayed puberty, weight gain, “round-face”, hairiness and stretch marks.

The goal and challenge of treatment is to eliminate signs or symptoms of EGPA using just the right amount of medicine. The medical provider strives to make that sure patients with severe disease get enough medicine, and patients with mild disease do not get too much medicine. While some symptoms may completely disappear with medication, others may continue due to ongoing inflammation. Some symptoms may persist because of permanent damage; thus, it is best to start with ‘aggressive’ treatment as soon as possible after diagnosis, before damage occurs. The first step in treatment is to achieve “remission” where the disease is not active. Once remission is achieved, less aggressive medication is provided that is sufficient to maintain this inactive disease state and prevent a flare-up. Corticosteroids will be weaned as much as possible during this “remission-maintenance” phase to a lower dose or discontinued entirely. Other immunosuppressive medications that are part of the treatment regimen may also be weaned if remission is sustained over a longer period of time.

At this time, there is no cure for EGPA. Serious complications of EGPA may include bleeding and scarring of the lungs, heart damage, infections, numbness, or rarely, death. However, with the increased knowledge of monitoring and treating this disease, including the variety of medications now available to treat EGPA, outcomes are improving. Regular and long-term follow up with a medical team is very important.

Some children with EGPA may continue to have relapses over many years. For those who are not having frequent relapses, then after a prolonged period of time (often years), steroid-sparing agents may be weaned to a lower dose or discontinued. For some patients, their disease will not return. Others may have a relapse or return of symptoms. This can happen right away or years later. Ideally, a relapse will be caught early if patients continue to follow with their medical team, before significant symptoms occur.

While there is less research on children with EGPA than adults, the disease itself appears to act similarly and follow a period of asthma, allergies, and elevated eosinophils. It is possible that children have a slightly different disease pattern as some differences have been seen in children versus adults with other forms of ANCA-associated vasculitis (such as more airway inflammation in children). It is important to recognize that children with EGPA may experience this disease during fundamental periods of physical growth and psychological development. Thus, mental health support is crucial to develop appropriate coping skills. Children may also metabolize medications differently than adults and therefore require unique dosing. It may also be more challenging for children to express their symptoms than adults, depending on the age of diagnosis.

Patients with EGPA require a coordinated team of medical providers. In addition to a primary care provider, a team may include a rheumatologist (autoimmune diseases), immunologist (immune system), pulmonologist (lungs), nephrologist (kidneys), dermatologist (skin), neurologist (brain and nervous system), cardiologist (heart), ear nose and throat specialist, physical therapist, psychologist and social worker. Ideally, these will be providers trained in the treatment of children (pediatricians). Typically, one specialist will oversee EGPA care depending on which part of the body is most affected. It may be helpful for parents and children to keep a journal of medications, symptoms, and questions in order to get the most out of their appointments. Patients and their families should feel empowered to speak up when concerned or wanting clarification.

No matter how mild or severe the disease, the toll of doctor appointments, laboratory testing, and medications can weigh heavily on children. It is important to find outlets for support, whether talking to a mental health therapist, engaging in physical activity, or connecting with other children with chronic disease. It is important to communicate with teachers at school, to make sure the child’s health needs are met without suffering academically. Ideally, children with EGPA will go on to live full and productive lives, however, ongoing follow-up with a medical team will be necessary.

American Partnership for Eosinophilic Disorders:

https://apfed.org/about-ead/eosinophilic-granulomatosis-with-polyangiitis/

While the Arthritis Foundation focuses on patients with arthritis, there are many resources available for children with any autoimmune disease including symptom management, school guidance, summer camps, and support groups.

https://www.arthritis.org/juvenile-arthritis

American College of Rheumatology Treatment Fact Sheets:

https://www.rheumatology.org/I-Am-A/Patient-Caregiver/Treatments

Paediatric Rheumatology International Trials Organisation (PRINTO) Resources:

https://www.printo.it/pediatric-rheumatology/GB/info/9/Rare-Juvenile-Primary-Systemic-Vasculitis

https://www.printo.it/pediatric-rheumatology/GB/info/15/Drug-Therapy

NIH Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center:

https://rarediseases.info.nih.gov/diseases/6111/eosinophilic-granulomatosis-with-polyangiitis

EGPA Videos

ACRVF Guidelines Conference: EGPA Breakout

Patient Heroes: Kate Tierney

Research Insights: Precision Medicine in the Treatment of ANCA-associated Vasculitis

Research Insights: Improving Diagnostics and Treatment of Small-Vessel Vasculitis