Vasculitis Types

About Central Nervous System Vasculitis

Last Updated on February 5, 2024

Central nervous system (CNS) vasculitis is a rare condition that affects the central nervous system, which includes the brain and spinal cord. Vasculitis causes inflammation of the blood vessels. This restricts blood flow and can damage the brain and spinal cord, and can cause loss of brain function, stroke and even life-threatening conditions.

Quick Facts

Unknown cases worldwide

Estimated 2-3 million US cases

Any onset age but generally peaks around age 50

Rare in children

More common in males

Ethnic prevalence unknown

Central nervous system (CNS) vasculitis is a rare condition that affects the central nervous system, which includes the brain and spinal cord. Vasculitis causes inflammation of the blood vessels. This restricts blood flow and can damage the brain and spinal cord, and can cause loss of brain function, stroke and even life-threatening conditions.

Vasculitis is classified as an autoimmune disorder, which occurs when the body’s natural defense system mistakenly attacks healthy tissues.

CNS vasculitis is typically categorized as primary and secondary:

- Primary CNS Vasculitis (CNSV) is vasculitis confined specifically to the brain and spinal cord. It is not associated with any other systemic disease (affecting the whole body).

- Secondary CNSV usually occurs in the presence of other autoimmune diseases such systemic lupus erythematosus or Sjögren’s syndrome; and systemic forms of vasculitis such as granulomatosis with polyangiitis, microscopic polyangiitis, or Behçet’s syndrome or viral or bacterial infections.

The cause of CNSV is not fully understood. It is believed that several factors may cause CNSV:

- An infection may contribute to the onset of CNSV.

- Environmental and genetic factors may play a role as well.

In general, CNSV is considered rare. In the case of primary CNSV, the disorder can affect people of all ages but generally peaks around age 50. It most often occurs in males.

Many forms of vasculitis are accompanied by fever, fatigue, and unintentional weight loss. CNSV symptoms may also include:

- Chronic headaches

- Strokes or transient ischemic attacks (mini-strokes)

- Swelling of the brain (encephalopathy)

- Forgetfulness or confusion

- Muscle weakness or paralysis

- Difficulty with coordination

- Abnormal sensations or loss of sensations

- Vision problems

- Seizures or convulsions

Diagnosing CNSV is challenging. It involves ruling out other diseases, infections, and conditions that have similar symptoms. There is no single diagnostic test for CNSV, so your doctor will consider a number of factors, including:

- Lab work: Blood tests are frequently normal in primary CNSV, but may be abnormal in secondary CNSV.

- Examination of the spinal fluid: A sample of the cerebrospinal fluid (surrounding the brain and spinal cord) is tested for infection and signs of inflammation. The fluid is removed by inserting a needle in the lower section of the back. This is called a spinal tap.

- Diagnostic imaging: Computed tomography (CT) scans and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can help identify abnormalities of the brain, spinal cord, and other organs and tissues. Computed tomography angiography (CTA) scans and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) are other imaging modalities that examine the blood vessels of the brain and are often included in the diagnostic workup.

- Cerebral angiogram: An angiogram dye (contrast agent) is injected into the blood vessels. X-rays are taken that can detect narrowing and blockages of blood vessels in the brain.

- Biopsy: This surgical procedure removes a small tissue sample from the brain. It is examined under a microscope for signs of inflammation or tissue damage. Because other conditions can cause brain abnormalities that are similar to CNSV, a brain biopsy may be necessary in trying to make a more definitive diagnosis.

RCVS is a group of conditions that involve spasm of the blood vessels in the brain. The symptoms can be the same as seen in CNSV. RCVS causes sudden, severe headaches, as well as strokes or bleeding into the brain. It is important for your physicians to be aware of RCVS in order to tell if the symptoms are from CNSV or RCVS. Treatment and prognosis are different.

The goal of treatment for CNSV is to reduce inflammation. This is done by using a high-dose glucocorticoid such as prednisone. For more severe cases, prednisone is used in combination with drugs that suppress the immune system’s response such as cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate mofetil or azathioprine.

Treatment may be more aggressive for the first three to six months and then tapered down as symptoms improve. In addition to medications, other forms of treatment may include physical, occupational and speech therapy. If memory is affected, brain activities that enhance memory are recommended.

The medications used to treat CNSV have potentially serious side effects, which include:

- Lowering your body’s ability to fight infection

- Potential bone loss (osteoporosis), among others

Therefore, it is important to see your doctor for regular checkups. Medications may be prescribed to lessen these side effects.

Infection prevention is also important. Talk to your doctor about getting a flu shot, pneumonia vaccination, and/or shingles vaccination, which can reduce your risk of infection.

Even with effective treatment, relapses are common for individuals with CNSV. If your initial symptoms return or you develop new ones, report them to your doctor as soon as possible.

Regular checkups and ongoing monitoring of lab and imaging tests are important in detecting relapses early.

Effective treatment of CNSV may require the coordinated efforts and ongoing care of a team of medical providers and specialists.

In addition to a primary care provider, you may need to see the following specialists:

- Rheumatologist (joints, muscles and immune system)

- Neurologist (brain/nervous system)

- Physical, occupational or speech therapist

- Others as needed

The best way to manage your disease is to actively partner with your health care providers and get to know the members of your health care team.

It may be helpful to keep a health care journal to track medications, symptoms, test results and notes from doctor appointments in one place.

To get the most out of your doctor visits, make a list of questions beforehand and bring along a supportive friend or family member to provide a second set of ears and take notes.

Remember, it is up to you to be your own advocate. If you have concerns with your treatment plan, speak up. Your doctor may be able to adjust your dosage or offer different treatment options. It is always your right to seek a second opinion.

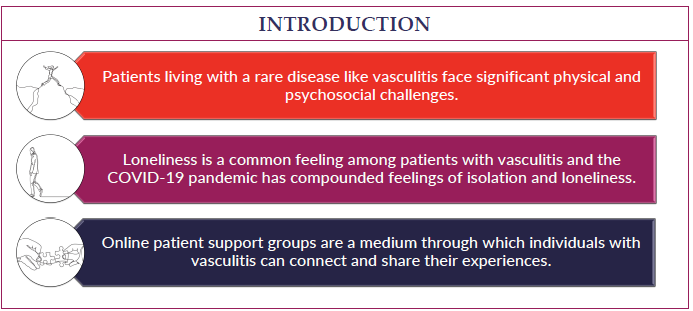

Living with a chronic disease such as CNSV can be overwhelming at times. Fatigue, pain, emotional stress and medication side effects can take a toll on your sense of well-being.

This can affect your relationships, work and other aspects of your daily life. Sharing your experience with family and friends, connecting with others through a support group, or talking with a mental health professional can help.

There is no cure for CNSV at this time. However, it is treatable. Early diagnosis and treatment are essential to prevent loss of brain function or stroke.

Even with treatment, relapses are common with CNSV, so follow-up medical care is essential.