Blog

Painting Her Pain: How One Woman Uses Art to Tell Her Vasculitis Story

When Dr. Shanali Perera chose to become a rheumatologist, specializing in vasculitis, she thought she’d chosen oneof the last specialties that looks at the entire body. “I thought I’d be like Sherlock Holmes,” she said, investigating the whole body, finding clues to her patients’ puzzles.

She had no idea her curiosity for investigation would soon hit so close to home.

It started with invisible “sensations” in her hands, legs, and face. “I was an atypical case,” she said. “I never fit into a box.” Her inflammatory markers were normal. Until palsy struck her face three years later, she looked fine. Doctors would examine her and think there was nothing wrong.

And Shanali was going to great lengths to conceal her illness. She was in the final stretch of her medical studies to become a rheumatologist and was determined to complete them. “I was doing all these crazy things just to get to work,” she said. Her 20-minute ride to work turned into two hours; her legs would “go dead” every 15 minutes, and she’d have to stop until the sensation returned.

“No one saw what it took behind the scenes to make it to work or get through my day,” Shanali said. “I just powered through.” When her right hand started to feel like a truck had run over it, she learned to write with her left. No one knew. They saw her at work and figured she was fine. Others stereotyped and dismissed her: she was a female medical registrar. “It’s probably just stress,” they’d tell her. Some assumed she was attention-seeking.

“It’s not that doctors weren’t sympathetic,” she explained, “but we’re trained to look at tests and we don’t always see the person…It’s like that famous quote, ‘Listen to the patient. They’re giving you the diagnosis.’”

For Shanali, being dismissed was worse than the symptoms; it felt like her integrity was being questioned, like “[her] word meant nothing.” After a while, she began to internalize these messages, wondering, “Am I imagining this? If no one can get to the bottom of it, is it real?”

For Shanali, being dismissed was worse than the symptoms; it felt like her integrity was being questioned, like “[her] word meant nothing.” After a while, she began to internalize these messages, wondering, “Am I imagining this? If no one can get to the bottom of it, is it real?”

After three years, her invisible symptoms refused to hide anymore. Shanali experienced extreme foot drops. Her legs got so heavy and the nerve pain so tremendous–like she was walking on knives–that she could only manage to walk 20 or 30 yards at a time. Eventually, she started using wheelchair assistance.

“Vasculitis is one of those conditions,” Shanali explained, “where you’ve got so many unrelated symptoms. If someone isn’t trying to align all the dots, it can take three to four years to diagnose.” That’s how long it took Shanali to get a diagnosis of secondary vasculitis and begin treatment, but her full diagnosis remained elusive.

As her disease management stumbled along and her symptoms progressed, she was forced to make the decision she had fought hard to avoid: she quit her job, ending her wish to practice medicine.

“Leaving my work,” Shanali said, “was one of the hardest days in my life. It felt like everything had gone out the window. Everything was lost–who I was, what I did; I was such a career-oriented person. I was in my early 30s. It felt like the disease stole my life in every aspect.”

When Shanali walked away from her career, she experienced a serious loss of identity. She said, “I felt derailed, like I was traveling on this speed train and everything went off the tracks.”

As she began steroid treatment, her body changed. “I was a tiny person before. I could not recognize myself in the mirror because who I was, and what I stood for, was distorted.” For a long time, she felt numb.

To Shanali, it felt like vasculitis robbed her of the freedom to move in every direction–physically, emotionally, socially, professionally. “How do I make sense of this?” Shanali started to wonder. “How do I find movement, again? How do I find meaning?” She felt like her vasculitis tried to disempower her.

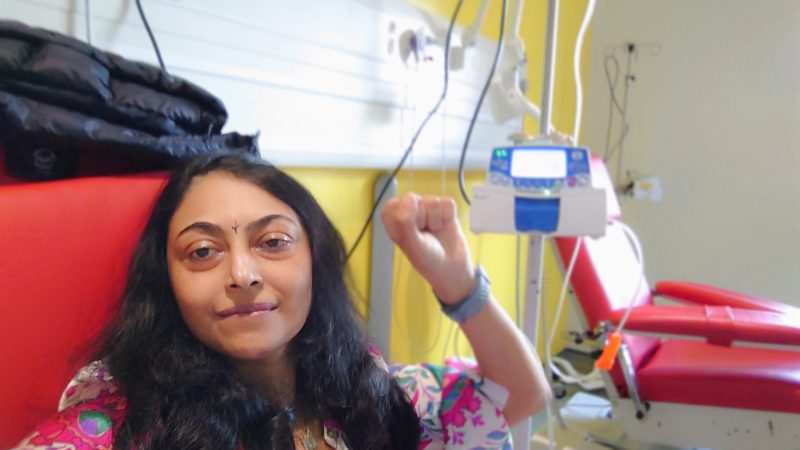

Seven years after her first invisible symptoms appeared, Shanali saw a glimmer of hope. New treatments began to make a massive difference in her life; she learned to walk, again. She felt called to embrace the new version of who she was. And she did something else: she started drawing.

It started on heavy fatigue days when all she could do was rest in her bed with her phone. She began to doodle using the Viber app. She added colors. It expanded from there.

Eventually, she transitioned to using acrylics on canvas. Describing her art, she said, “The most serious things I’ve created I’ve drawn with my pain.” When she can’t use a paintbrush, she throws the paint onto the canvas. It can be painful to create, but it feels like all of her goes into her art. “It gives meaning to the painting,” she said.

Art became Shanali’s tool to help her cope, to help her regain a semblance of control over her life. “This journey is not easy. You need to have a tool,” she said. It can be anything: art, gardening, music, cooking. Her mission now? To empower people to find their outlet, and themselves.

Today, Shanali shares her art with the world, including using it to raise vasculitis awareness. She has a new book called, Finding Me Beyond Illness, where she uses art to depict what it’s like to go through an illness journey. She wants it to be a conversation starter, to help close the gap between people living with chronic disease and those trying to treat it or help from the outside.

Today, Shanali shares her art with the world, including using it to raise vasculitis awareness. She has a new book called, Finding Me Beyond Illness, where she uses art to depict what it’s like to go through an illness journey. She wants it to be a conversation starter, to help close the gap between people living with chronic disease and those trying to treat it or help from the outside.

“Having my own creations,” she insists, “and being able to share them is empowering. It gives me purpose and meaning. For a lot of us with vasculitis, it’s difficult to face each day. Now, I see that we need to find the beauty in all the ugliness around us. Because even though the illness can be very disheartening and distorting, there is beauty. We mustn’t forget to acknowledge it.”

For years, Shanali felt lost. In the wake of her illness, she couldn’t tell who she was. Towards the end of our conversation, I asked her who Shanali is now.

“I think Shanali is still evolving,” she said. “I’m still trying to find the truest version of me. I’m a lot more free now. I think this new version of Shanali is more daring.” She went on, “The new Shanali is trying to live. I’m going to be the love that surrounds me.” In fact, her next art piece will be just that: an embodiment of love.

Her mantra these days? “I am not the illness. I am Shanali first. The illness is only a part.”

Despite years of struggle and, even now, continued flares, she is determined. She’s lighting up her imagination and wondering: “What can I do next?”

Author: Ashley Asti